The Traffic Light Trap

Or Why Germany has so few roundabouts..

I am waiting at a red light at a big intersection on my bike when I hear sirens behind me. I move my bike out of the way so cars can let an ambulance find a path through the traffic. I block my ears as the ambulance speeds past me and through the red light. Then comes a loud crash. A car approaching the crossroad from the left has soared past his green light and smashed into the side of the ambulance. Smoke pours out of the front of the car which is completely buckled. Luckily the air bags inflated, and the driver looks relatively unscathed. But the car is a write off. Presumably the driver thought he could rely on the green light and he didn’t see or hear the ambulance racing through red.

I have always wondered about Germany’s reverence for traffic lights. On my first visit to Berlin in the 1990s, I saw scruffy anarchists wait for the green man before venturing onto a pedestrian crossing, even late at night with no cars in sight. Obviously, traffic lights are essential at big city crossroads like the one where I saw the accident. But Germany has lights even on small rural intersections, rarely trusting drivers to make their own decisions about whether it is safe to proceed. Roundabouts, which are much more common in Britain, are more taxing for drivers, but research shows that they are generally safer, allow traffic to flow faster and are cheaper to maintain.

In his book “Brave New Work”, consultant and entrepreneur Aaron Dignan argues that many organisations treat their employees like the German state treats its drivers, preferring systems of control and compliance that operate like traffic lights, rather than the trust and autonomy epitomised by a roundabout.

“We have a lot more command and control than we need and it’s holding us back. In most organisations, the operating system says on paper “We hire the best people and we trust them and they have these ambitious goals.” And then we treat them like they’re five years old. It’s bonkers,” Dignan says.

Dignan suggests that in today’s dynamic and unpredictable environment, organisations need fewer traffic lights and more roundabouts. Managers should trust staff to use their own judgement and to stop and go at the right time.

Which brings me back to Germany. Reading Dignan’s analysis of organisations made me realise why I still sometimes struggle with German culture even after living in the country for so long.

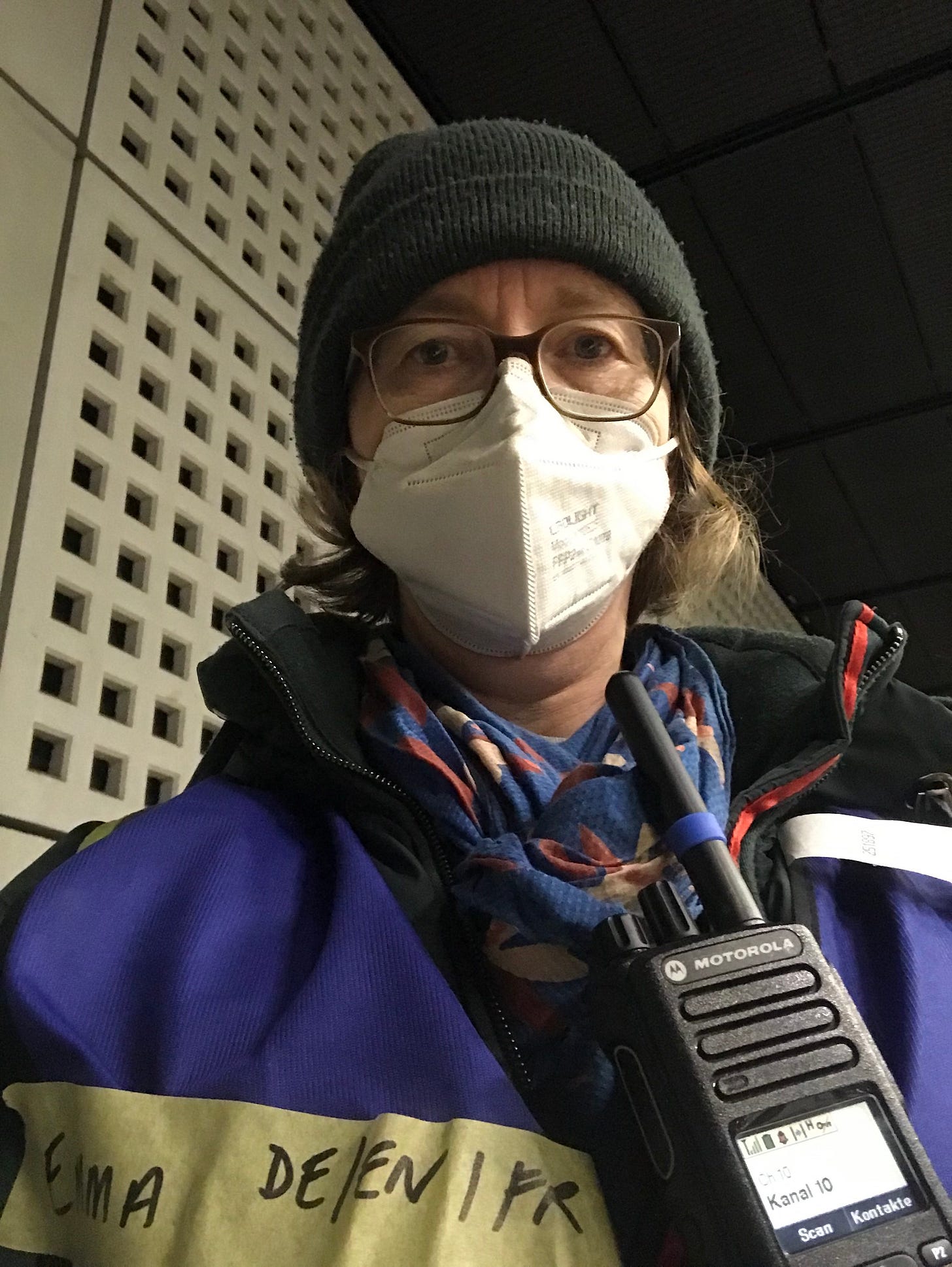

In 2022, Berliners showed a heart-warming outpouring of goodwill by turning up at the main station to help disorientated Ukrainian refugees find a place to stay or plan their onward journey. I decided to join them and soon found myself armed with a megaphone and a walkie-talkie at the central station. We quickly became a slick operation that received donations and handed out clothes, food and toiletries to thousands of mostly women and children arriving in Berlin every day.

But as the weeks went by, German regulation and bureaucracy slowly throttled our efforts. There were good reasons for this: police feared that human traffickers might pose as volunteers to exploit vulnerable women and children arriving in Germany. I ended up doing shifts to onboard and help manage the work of the volunteers. Soon it felt like we were spending more time briefing volunteers on the rules and checking and recording their IDs and COVID vaccination status than helping the new arrivals.

Many volunteers (particularly the non-Germans) bristled at the lengthening list of regulations. On my last day in the station, a German student with a clipboard shouted at me because I had allowed a Ukrainian woman to take a luminous orange volunteer vest for her 12-year-old son, who also wanted to help. Rule 150 on the briefing checklist: No under-18s allowed.

After watching my two teenage sons navigate German schools, I guess that student’s penchant for command and control stems from an education system that doesn’t promote much personal responsibility and initiative. When we considered switching our older son to a school offering the International Baccalaureate, the admissions officer said students who were used to the German system can struggle at first with the autonomy expected from a style of learning based on trust and self-motivation.

Of course, the traffic light/roundabout dichotomy is a gross simplification, both of national and organisational cultures. Many Germans prefer autonomy and many Brits love rules (we did come up with the regulations for many of the world’s top sports). Most German playgrounds would be deemed unsafe by the notorious British “health and safety” inspector. And while German schools can seem rigid and old fashioned to a Brit, German children are granted much more autonomy in other ways, such as being expected to walk alone to school from a young age. (Of course, their parents can be pretty sure that they will wait for the Green man when crossing the road.)

In his book “Reinventing Organisations”, Friederic Laloux says it is this kind of autonomy that some of the most forward thinking companies and teams are trying to cultivate, moving beyond command and control hierarchies towards self-management, in a bid to make work more productive, fulfilling, and meaningful.

That sounds like a worthy goal, but I am not sure that all employees want, or thrive in, organisations that grant them a large amount of freedom. After growing up in an era of financial insecurity, layoffs and hustle culture, many young people today say they would prefer a steady, secure 9-5 job, with the government for example, while they pursue their real passions outside of working hours. The hashtag #governmentjobs has already racked up over 22 million views on TikTok.

With that in mind, here is a quick poll.

What I am reading:

Work - A History of How We Spend Our Time - James Suzman - a fascinating book by an anthropologist who has spent a lot of time with the Khoisan peoples of southern Africa that questions many of our economic assumptions.

“Contrary to the current narrative that the marketplace is a hotbed of kill-or-be-killed competition, for much of history people in similar trades usually cooperated, collaborated and supported one another.”

The Culture Map - Decoding How People Think, Lead, and Get Things Done Across Cultures - Erin Meyer - I found this exploration of cultural differences so fascinating that I will probably dedicate a future blog to discussing it!

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow - Gabrielle Zevin - despite the rave reviews, my hostility towards my sons spending so much time gaming made me reluctant to read this book about a friendship between two video game developers. But the characters quickly drew me in and it even helped me understand the attraction of gaming a bit better. (I still wish my kids would read more books instead…)