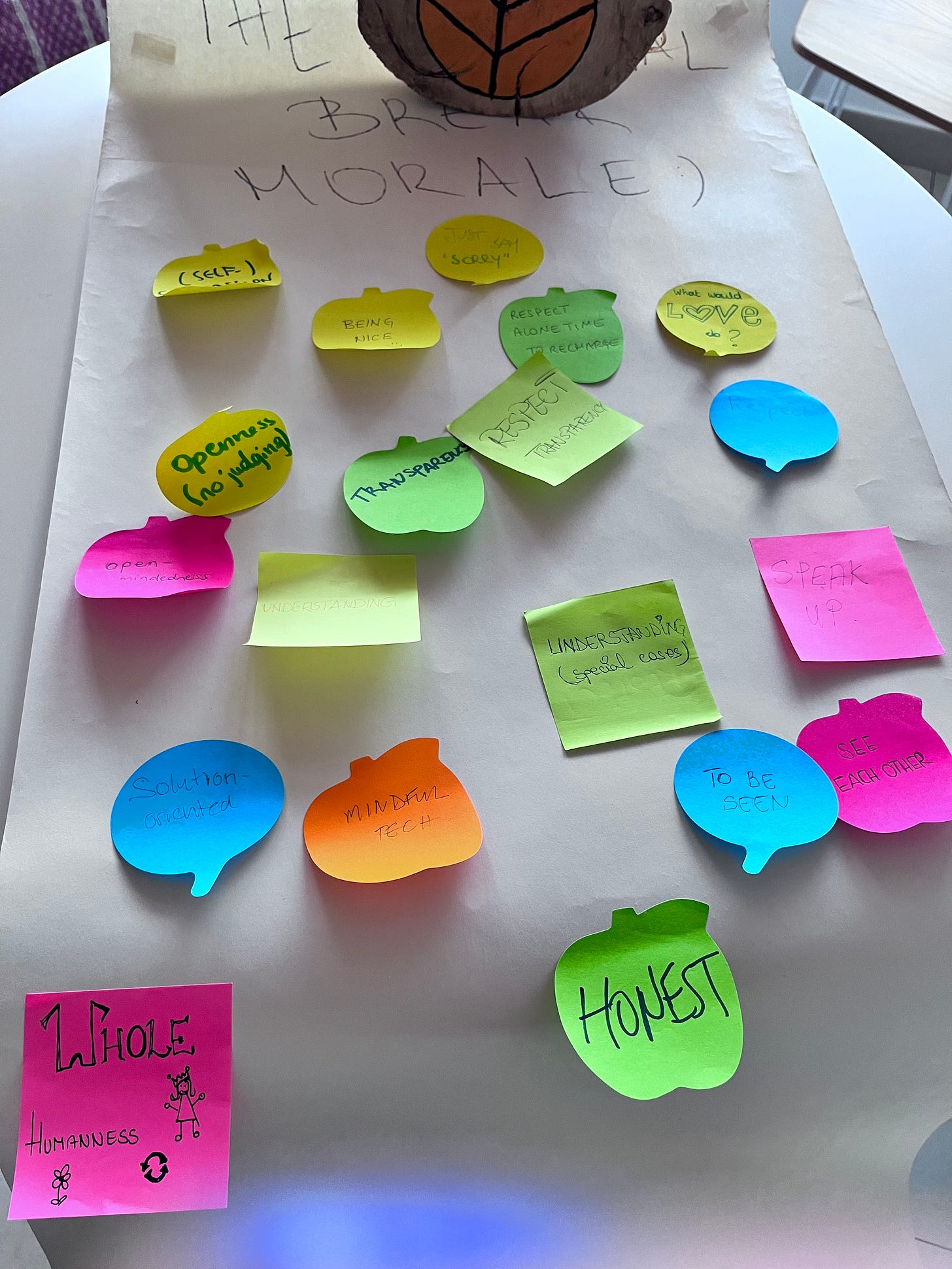

I am sitting in a circle of women, twisting an orange Post-It note in my hands, trying to pluck up the courage to speak. All the other women have already stuck their contributions on the wall and now it is my turn. We are discussing what values are important to us to ensure a collaborative environment while we live and work together for four weeks in a Spanish village as part of a fellowship for women entrepreneurs. The other woman have mostly chosen uncontroversial values: understanding, respect, transparency. But I want to address a value that I am pretty sure will be divisive. I don’t want to stoke conflict, so I keep quiet until last.

As often happens in situations like these, my version of the “Good Girl Syndrome” kicks in. The syndrome describes typical behaviours that society instils in girls and women including:

* a fear of disappointing others

* a desire for perfection

* obedience to rules

* a reluctance to speak up

The latter is my foible, especially in situations when I am worried about provoking conflict.

When everyone else has spoken, all eyes turn to me, and I have no choice but to come forward with my Post-It: I wrote “Mindful Tech” on the apple-shaped paper. I explain that I am uncomfortable with the assumption that all our communication and group activities will be organised on Big Tech platforms that I don’t want to dominate my life, and which I don’t use regularly on my phone. And I encourage the other women to put their phones away and enjoy the beautiful scenery around us without constantly feeling the urge to photograph it and share it online. As one of the oldest women in the group, I feel like a prophet from a bygone age among all the digital nomads.

In the end, I say my piece, flushing red in the face as I literally get hot under the collar about the topic. One other woman says she doesn’t want to be made to feel guilty for her love of photography. But I survive the mild discomfort of the situation and we agree to disagree and move on. It is a good reminder that these typical “female” behaviours can still hold me back, even in such a supportive all-women environment.

Good girls never feel good enough

The day before, the 18 women on the fellowship in Benarrabá sat together outside and introduced ourselves. Tears were shed as we opened up about the life paths that had brought us to this point. The topic of the “good girl syndrome” came up repeatedly, in different contexts among these women from across the globe: Germany, Romania, Canada, Croatia, Bulgaria, Russia, Belgium, Italy, France, Ireland, Colombia, Austria, the UK, Sri Lanka, Vietnam and North Korea were all represented. Despite our diverse heritage and ages (ranging from 26 to 52), many of the women felt they had to be “good” when they were growing up to meet to the expectations of their families or their communities. That resulted in them pushing themselves too hard to achieve, or to fit in, or to make others happy, losing touch with their own desires, voices and needs in the process. Several of them said that had made them feel like they were “never good enough”.

Three quarters of women suffer the syndrome

Afterwards I decided to do a straw poll: of the 18 women on the fellowship, all but four admitted they had suffered from the good girl syndrome at some point. Perhaps this group is not representative, but it is still striking that over three-quarters of these high-achieving, outwardly confident women have felt this way.

This is a topic I have thought a lot about recently as I have spent time in classrooms talking to teenagers for my media literacy project. The girls are usually keen to cooperate with the teachers and get the right answers in their quest for good marks, while the boys often slouch in their chairs or scroll secretly on their phones. A teacher friend worries that our education systems supercharge the good girl syndrome by rewarding compliant, controlling and perfectionist tendencies that will not serve these girls well in the real world. And social media means that these behaviours are also being stoked outside of education too, with girls seeking to perfect their appearances as well as their grades.

Meanwhile, many boys seem to do just enough to get by. They are less paralysed by perfectionism are better able to swagger through life. While I am not exactly keen on the amount of time my teenage sons spend online gaming, at least they are still playing, shouting joyfully to each other as they score an online goal. Meanwhile, many of the girls of the same age are trying to match up to unrealistic beauty myths they see perpetuated on Instagram.

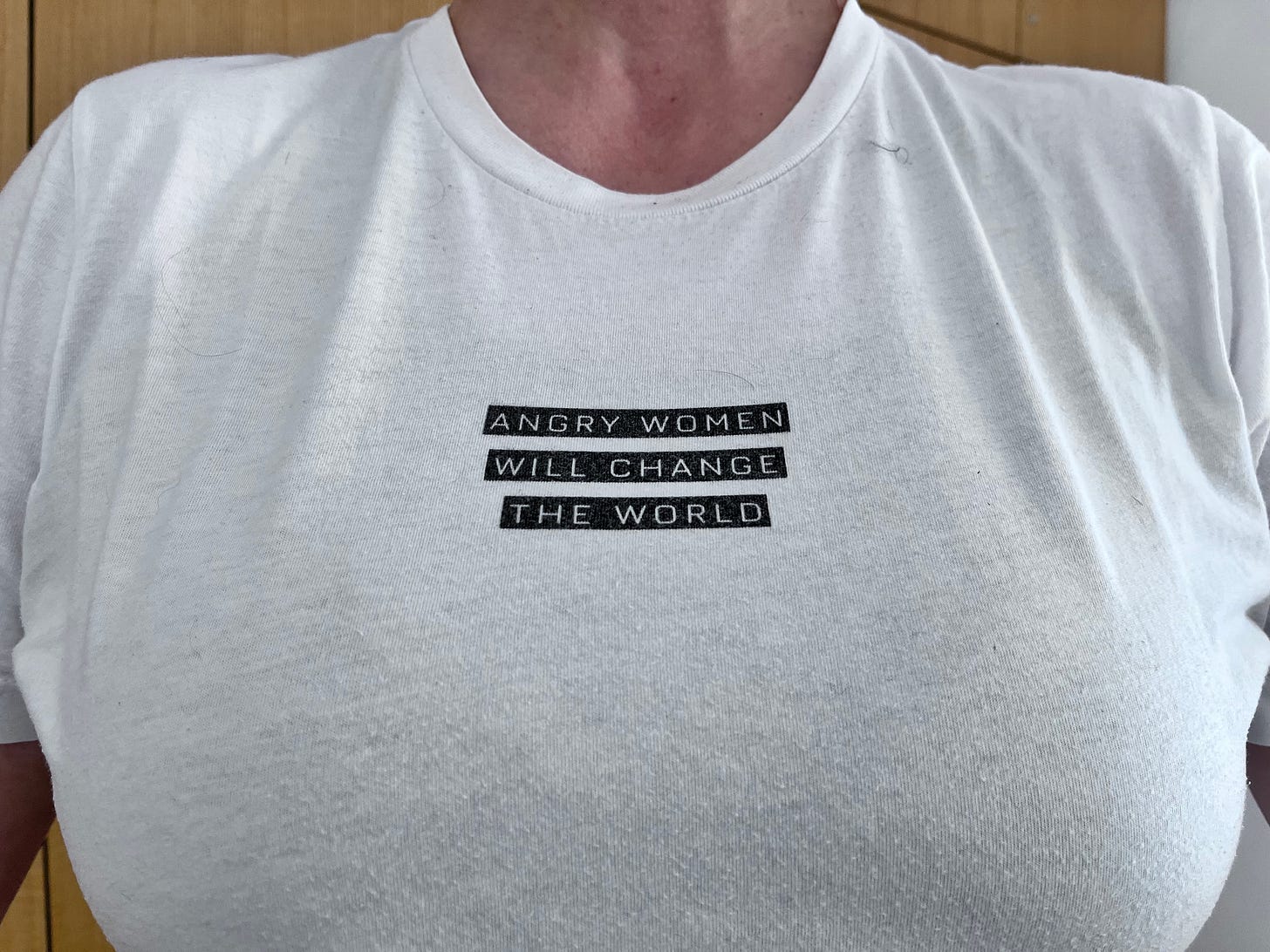

Angry women will change the world

Good girls often learn to suppress their playfulness due to a fear of failure, and of looking silly. But they also tend to suppress their rage. I feel rage about the impact of tech on our lives, particularly on our children, but usually bottle it up because I feel impotent against the might of Silicon Valley, and ashamed of my own digital addiction.

Expressing my irritation about phone use during this fellowship perhaps had a small impact, along with the digital detox of this beautiful place. When we met up with another group of women on the fellowship who have spent their time in the city, it was striking that they were all scrolling on their phones during a presentation, while my group was paying attention to the speakers, phones mostly out of sight.

I met a former colleague recently at a conference and told him I had completed a training course in coaching and was starting my own business as a coach and a consultant. He guffawed: “Why did you need to get a qualification? Any man with your experience would have just set himself up as a coach and made it up as he went along!” That conversation again brought home to me how differently men and women operate. A woman will only apply for a job if she meets all the requirements in the job description, but a man will be comfortable putting himself forward even if he is not really qualified.

Fix the system, not the women

I have even thought of creating a course called “how to blag like a boy” to teach women a bit more swagger to help them overcome the good girl syndrome. But then I ask myself whether the answer to women’s lack of confidence is to just get us to behave more like men, fixing ourselves rather than fixing the system that perpetuates inequality. Instead we should value the qualities that girls and women bring to the table, their quiet striving, their close relationships, their desire to keep learning new skills and bring others along with them.

Those have all been on display during this precious time in Spain with other women, sharing our expertise, encouraging each other to believe in ourselves and to speak up. One of the women in the group who said she does not suffer from the good girl syndrome as she was brought up by a Russian mother to be fearless and rebellious described herself as a “bad girl who’s becoming a good woman”.

When we held another session to review our values, I added: “Don’t be afraid to speak up” on a new post-It. And I have found myself expressing my needs and opinions more often as the fellowship progresses, instead of keeping them to myself. So, when my back started aching while sitting on the ground during a mindfulness exercise, I asked if it was OK to lie down. Several others followed suit. Speaking up is still uncomfortable for me, but I am making progress.

I loved it Emma, such a powerful message. Thanks for sharing a bit of your soul through this lines at Benarrabá with Rooral. We really enjoyed meeting you and wishes you this messages go around the globe to make impact.