When a massive blast shook Beirut on August 4th, 2020, many Lebanese assumed the city was under attack by Israel. They quickly realised that this was quite different from the air strikes they remembered from the 2006 war with their neighbour. Thousands of tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored at the port had detonated. The explosion killed more than 200 people and injured 7,000, many hurt by flying glass as the blast wave flattened buildings and shattered windows.

Part of the reason I have not written for so long is because I was in Beirut in September to run workshops for local journalists on mental health and online harassment. I am glad they got the chance to address the topic before the country is gripped by the fear that it could be drawn into the conflict that has erupted in Israel.

At least on the surface, the city has been quick to rebuild after the disaster. Apart from in the immediate vicinity of the port, Beirut carries more scars from the 1990-1975 civil war than from the explosion. The abandoned Holiday Inn hotel that was a battle zone in the 1970s still towers over the city centre.

Journalists in Lebanon have faced mounting risk of both physical and cyber attacks since anti-government protests erupted in 2019. Their situation has become even more precarious as they have sought answers to the port explosion and the economic and political crisis that still grips the country.

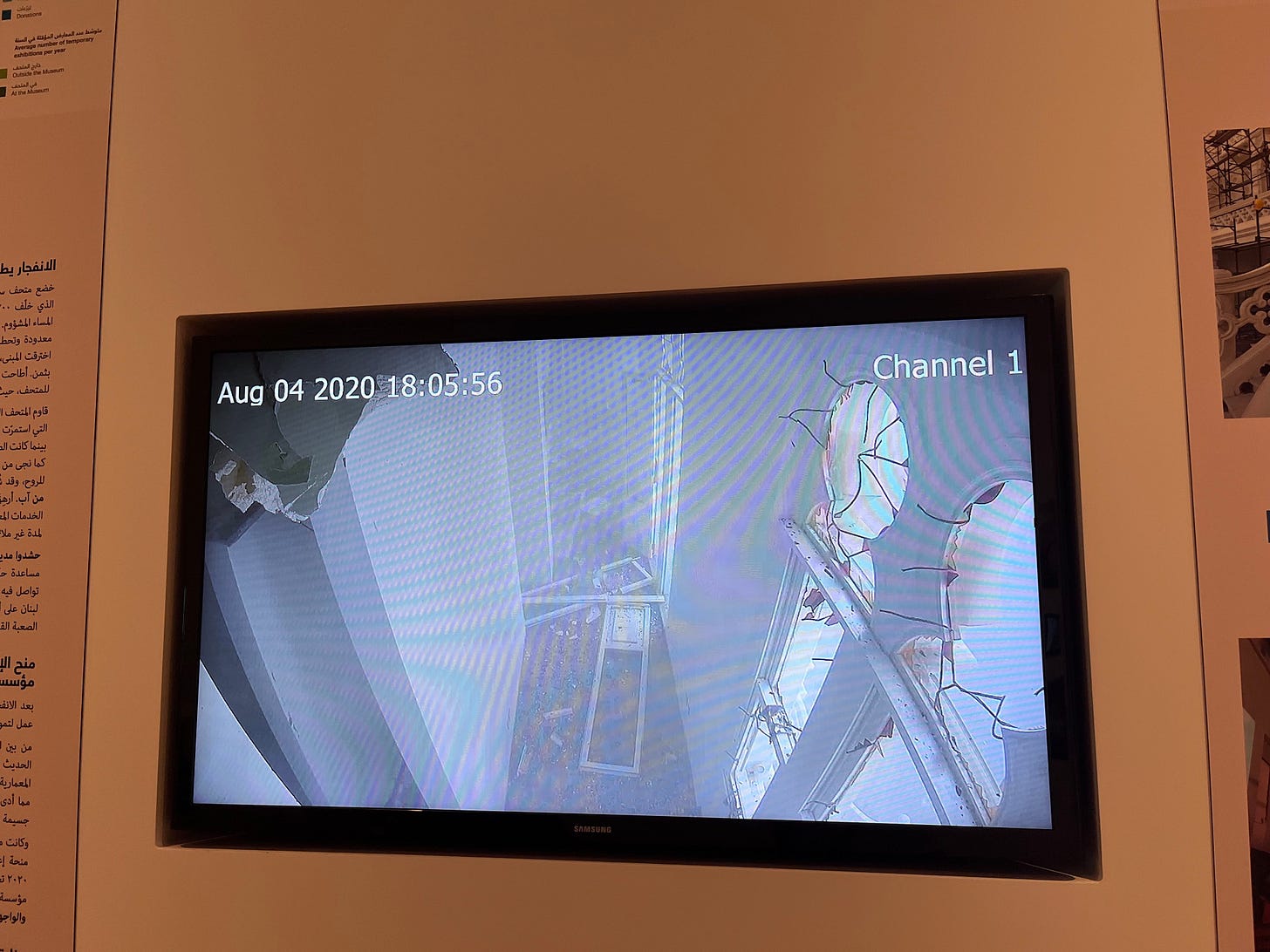

In the aftermath of the port disaster, armies of volunteers swept up the debris and repaired thousands of damaged windows and buildings. One symbol of that recovery is the Sursock museum that is just 800 metres from the port. The blast tore through its colourful windows, which had only recently been restored, and damaged dozens of paintings.

In this tormented country, the gallery has been repeatedly forced to close since it was bequeathed to the nation by art collector Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock. The museum reopened in May for the fourth time since 1961 after $2 million of repairs.

Art as therapy

It is a monument to the power of art as therapy. Paintings on display show the pain suffered by this country but also its creativity. Small private galleries are dotted around the city and seem to be doing a brisk trade in paintings and sculpture from across the region, even on a Friday evening. I took part in a bit of art therapy myself when I joined a workshop run by the wife of my Lebanese co-trainer and learnt the Japanese technique of hammering petals and leaves into fabric to create natural dye, a great way to release tension.

Reporting on the devastating explosion was just the latest trauma suffered by the journalists in my workshops. The year before the blast, a financial crisis resulted in a run on the Lebanese pound, wiping out most of the savings of ordinary people. (It cost me one million Lebanese Pounds for a ticket for the National Museum – or about $10). The economy is propped up by remittances from those who have fled the country since the civil war. The exodus has continued. At the airport, most of the “foreigners” queuing with me at passport control were back to visit family.

While my task in Beirut was to help journalists understand and deal with trauma, stress and harassment, I learned just as much as I could teach them.

The will to survive

After the workshop, I visited Beit Beirut: a grand house on the dividing line between the warring factions during the civil war that became a snipers nest. The building has been turned into an exhibition space, but left open to the elements on one side, the walls still pockmarked with bullet holes and sniper graffiti.

This sign, accompanying an exhibition of historical photos, summed up the spirit of Beirut:

“Despite all the catastrophes and setbacks, the characteristic of the city and its people is the will to survive, believing that from calamities and destruction, new life will always emerge from the ashes, heralding a better future.”

Family ties strengthen resilience

Studies suggest that children growing up in even the most deprived of circumstances will be better equipped to deal with problems later in life if they had at least one adult they could rely on in early life. And close family ties are clearly on display in Lebanon. On a seafront walkway not far from the devastated port, I saw fathers teaching children how to fish, while grandmothers sat around shisha pipes and couples took sunset strolls. The seafront also illustrates how the wealthy are profiting despite the crisis: it is lined with luxury apartments, yachts and shiny SUVs. Playboys threw up spray as they raced each other on jet skis.

Meanwhile, the journalists trying to hold this elite to account fight on, many of them supplementing a meagre wage from journalism with other work. Others are supported by relatives working overseas.

A friendly troll?

One of their coping strategies is laughter. Although several of the journalists had dark rings under their eyes, the training room was often full of gallows humour, even when we were discussing difficult topics, including about the “electronic armies” who try to intimidate journalists, particularly those working on topics like women’s rights and LGBTQ issues. One of the reporters giggled as she showed us the latest horoscope sent by one of her trolls.

My co-trainer for the workshop, a Lebanese therapist, said most people had reacted to the blast in one of two ways – either by suffering from heightened anxiety or by making the most of every day and seizing pleasure where they can.

Many people bury their trauma: it took two days before the journalists at the workshop talked about the blast: one described her sensitivity to loud noise, even when visiting another country; another had flashbacks after he spent days reporting on the disaster. I sensed some felt survivors’ guilt: their own experience of the destruction of part of their home city pales in comparison to those who have lost loved ones or their homes.

And this latest horror just compounds earlier pain. One participant mentioned in passing that her father had been kidnapped during the civil war and never heard from again. Such experiences seem so commonplace that people appear to shrug them off.

Before leaving Beirut, I made a quick visit to the National Museum, which again underlined the country’s resourcefulness. Lebanon changed hands numerous times in its history as empires rose and fell, and it suffered several major earthquakes, but always bounced back.

The collection includes exquisite Phoenician statuettes, marble sarcophagi and Roman mosaics, many of which were hidden in the basement and walled up during the civil war. It made me realise how backward ancient Britain was in comparison: the top archaeological discoveries made Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland include a toilet seat, some boxing gloves and leather shoes. It just goes to show that if you have the luxury of sunshine and fertile soils, you have more time to produce beautiful works of art than if you are battling to stay warm while defending a windswept fort.

“Problems cause species to evolve”

Lebanese author Amin Maalouf sounds like he might prefer chilly Northumberland to the sunny Mediterranean.

“I have always thought that Heaven invented the problems and Hell the solutions. Problems jostle us, knock us about, make us lose our complacency, take us out of ourselves. It is healthy to be thus thrown off our balance; it is through problems that all species evolve; it is solutions that cause them to stagnate and become extinct.”

That comment jumped out at me from Maalouf’s book “The First Century After Beatrice” that I found in a dusty second-hand bookshop in Beirut.

The Lebanese are certainly a nation of problem solvers: the fact that municipal electricity and water provision are unreliable means that private companies supply generators and delivery of drinking water by truck.

Being thrown off balance also sparks great creativity. In the basement of the Sursock Gallery, composer and visual artist Zad Moultaka has made something beautiful in processing the explosion. He took digital images of every artwork in the permanent collection and projected them on white blocks as streams of colourful fragments accompanied by the sound of breaking glass and roaring winds.

Nearby, visitors have scrawled messages all over the wall of the museum as part of an attempt at healing: “To this beautiful city that will eternally stand and whose soul no one can destroy,” wrote Rozan.

What I’ve been reading (I see a resilience theme in all of them…)

The Port of Beirut - Lamia Ziade - a haunting illustrated account of the explosion and the history of the port told by a Lebanese emigre to Paris.

Black Butterflies - Priscilla Morris - a beautiful fictional exploration of the siege of Sarajevo that explores humanity and the power of art in impossible circumstances.

My Brilliant Career - Miles Franklin - a story written in 1901 by a young girl growing up on a farm in the Australian outback with an alcoholic father. She survives drought and finds sanctuary in literature.

As the Women Lay Dreaming - Donald S. Murray - a novel about how a community and a family respond to the Iolaire shipwreck off the Isle of Lewis that killed some 200 servicemen on the last leg of their journey home from World War One: “There is a negative side to forbearance. Lips can be buttoned too long, views and opinions left unexpressed.”