Do you need rules at work?

What Adidas, Netflix, Reuters and Zalando teach us about workplace culture

Berlin has had a makeover in the last two decades. Once “sexy but poor”, as a former mayor described it, it is now . . . less sexy and a bit less poor. The city is still not rich by German standards, but it is now too expensive for the sexy, creative people who lived in squats and partied in underground bars after the wall came down.

The gentrification started with an influx of politicians, civil servants and journalists like me after the German capital moved from Bonn in 1999. But it really accelerated in the last 15 years as the city became a magnet for start-ups companies like online fashion firm Zalando and mealkit maker HelloFresh.

When I first started reporting on Zalando in 2013, I went to a party to say goodbye to their office in a funky converted industrial building. The team was still mostly made up of recent graduates, who worked and played together hard. But in 2014, Zalando went public and moved into more corporate buildings, as it hired thousands of new staff.

The fresh-faced founders wanted to cling on to the vibe that had made the company special, even as it grew and they developed their first wrinkles. In 2016 they introduced "radical agility", a method first used in software development that combines more autonomy for employees with continual learning.

Can employees be trusted?

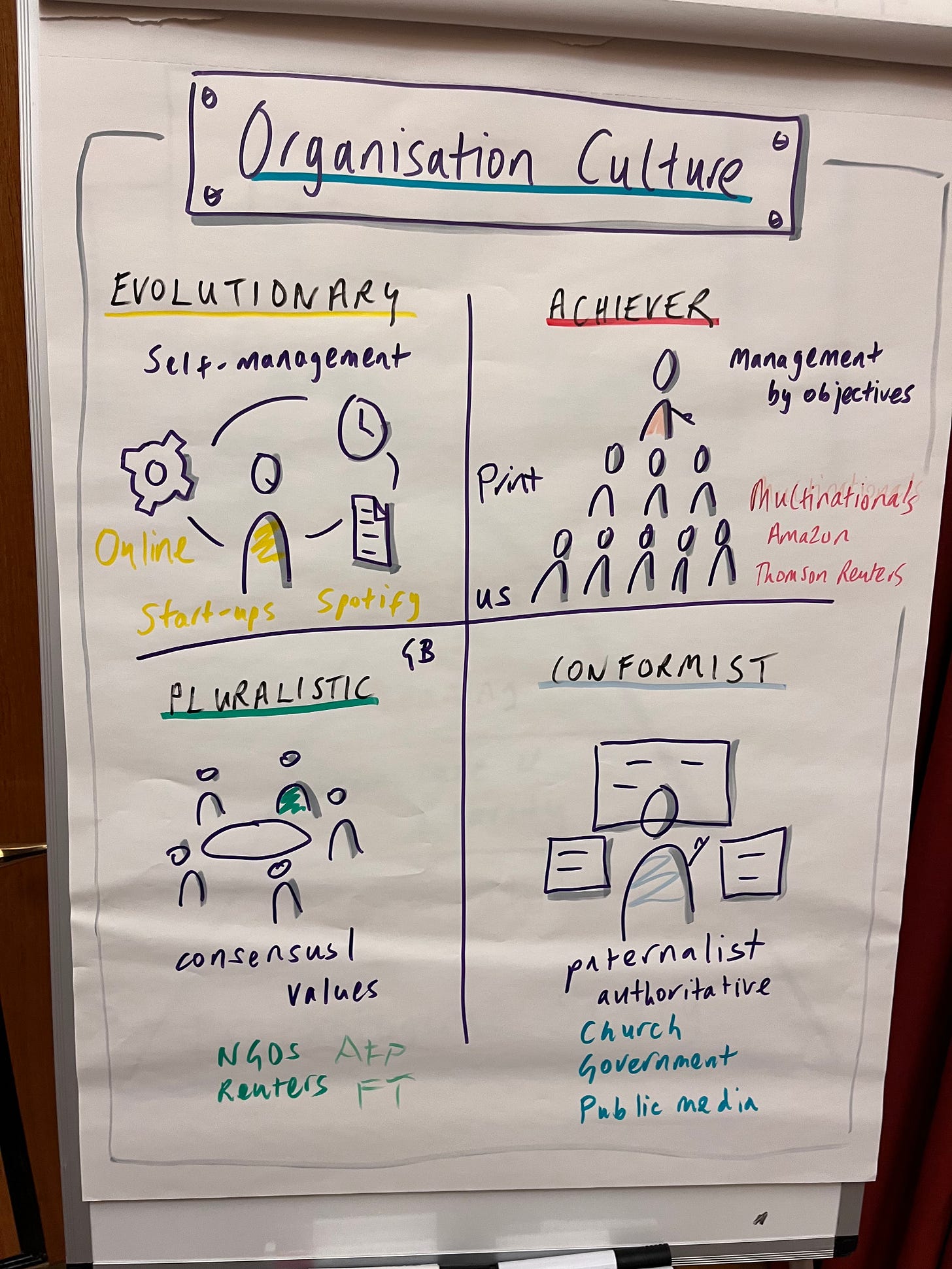

In his book Reinventing Organisations, executive advisor Frederic Laloux describes this as an “evolutionary” culture, which replaces strict management hierarchies and formal targets with freedom for employees to manage themselves.

He contrasts this “evolutionary” culture with “conformist” organisations like government and the military which have strict hierarchies and a more paternalist, top-down style of management, with leaders determining both what and how the job should be done.

He says many big multinationals have moved on from conformism to become “achiever” organisations, where the main goal is to beat the competition and achieve profit and growth. Management is based on setting objectives about what should be done, while staff have more freedom about how to achieve them.

The next step in his model of management enlightenment is the “evolutionary” culture embodied by companies like Zalando and other start-ups.

Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings took the idea to extremes with his “no rules rules” philosophy. Netflix demands excellence in return for staff freedoms such as taking as much holiday as they want, working whenever they want and allowing staff to buy whatever they need without getting permission. The principles aim to maximise “flexibility, speed, and boldness” through a rapidly growing organisation.

Meanwhile, in the world of non-profits and academia, Laloux says the most common organising principle is “pluralistic”, with leadership based on consensus while employees are usually motivated by common values and an ethos of service.

I have seen all of these cultures at the media organisations I work with, but the most common one is the “pluralistic” that seems especially suited to most journalists’ desire for flat hierarchies and organisation based on common values. However some of the big ones, like my former employer Thomson Reuters, have more of an “achiever” culture, which can grate with the lone wolf ethos of many reporters.

Culture clash is inevitable

Different countries favour different styles: the “evolutionary” model clearly has its roots in the Californian counterculture of Silicon Valley, while the hard-driving “achiever” style is common in global multinationals. The pluralist archetype seems more common in consensus-driven Europe, while Asian companies often favour the hierarchies of a “conformist” culture.

In my courses and consulting, I ask managers to think about what culture is most common at their organisations: leaders at public broadcasters often report having a more top-down conformist style, like other state-run companies. Digital or online departments of big media companies might emulate the self-management of start-ups, while print divisions are often more wedded to a sales-first “achiever” style.

Of course, different parts of an organisation can have different cultures: at Zalando, the self-management philosophy was focused on tech teams rather than warehouse staff, who are subject to a more traditional command-and-control hierarchy.

Much depends on the personal style of those at the very top, as I discussed in my last newsletter. It is often the visionary “pioneers” who prefer an “evolutionary” culture, while an “integrator” manager might prefer a “pluralist” organisation.

A mismatch can lead to a culture clash, as I observed when I reported on Adidas. Herbert Hainer was CEO for 15 years and his “driver” leadership style fitted well with the competitive “achiever” culture of the world’s second biggest sportswear firm. His successor Kasper Rorsted had more of a “guardian” style that might have gone down better in a “conformist” organisation. His contract was ended early and he was replaced by Bjorn Gulden, who I would put more in the “pioneer” category, perhaps a better match for a company trying to reinvent itself and revive flagging sales.

Under Hainer, Adidas had already tried to inject more of an innovative culture by copying the trendy open-plan design more common at start-ups when it was designing a huge new office building at its headquarters in Bavaria.

But architecture is not enough. Any leader who wants to consciously shift culture of needs to plan carefully and communicate well. One big media company I have supported is trying to inject more of an “achiever” ethos to its “pluralist” vibe to help it respond to the intense demands on our industry, but it needs to be conscious of taking its journalists along with it.

After the Canadian company Thomson bought Reuters in 2008, the company gradually morphed from a British to a North American culture, away from the cosy club that was a bit like working for the British foreign service, and towards something more corporate and “achiever” focused.

The company’s top leadership shifted from London to New York. Change was gradual but it was hard for many senior Reuters staff to embrace and many of the old guard eventually left. Reuters became more hard driving and won several Pulitzer prizes, but lost something of its family feeling in the process. Now the company is led by Italian Alessandra Galloni, who started her career at Reuters but then worked for a decade at the Wall Street Journal. She is better placed to straddle the old and new cultures.

In reality, organisations need a touch of all of Laloux’s cultures to suit different departments, tasks and employees. They must foster innovation, promote performance, motivate their people, and create structure and process. But depending on the style of the top leadership and the demands of their level of growth, they might emphasise one or two of these as their guiding principles. The most important is to do this consciously and not just expect culture to sort itself.

That is especially true when times are tough and organisations have to shrink. That is happening now at many media companies, and even previously fast-growing start-ups like Zalando. Job cuts can be corrosive to any company culture as I know well from years of rolling redundancies at Reuters. It is precisely at those times that leaders need to be most intentional about creating a caring culture to keep those who survive the cull engaged.

What I am reading:

James by Percival Everett - A recasting of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn told from the perspective of Huck’s friend Jim/James, who is an escaped slave. The best aspect of the book was the insight into the linguistic code-switching of slavery. It sparked a lively debate at my book club about other revamped classics, such as Julia by Sandra Newman (a retelling of 1984), as well as reversed narratives like Blonde Roots by Bernadine Evaristo, which imagines Africans as masters of white English slaves and The Power by Naomi Alderman, in which women become the dominant sex.

All Fours - Miranda July - an explosive book about a woman’s menopausal awakening that I devoured: “Imagine what it feels like to be a man. No cycles. No deaths-within-life. No transformation from one kind of person into another…. for the world… we performed sameness.”