Do better teams make more mistakes?

How openness about errors can promote innovation and collaboration

When I led the Reuters bureau in Amsterdam, my boss set me a target that initially made a lot of sense. I had to cut the number of errors in the articles produced by my team. In fact, I had to make sure that fewer than 0.5 percent of stories needed to be corrected.

It is a mortifying process: it is almost as if somebody has scrawled graffiti over the top of your carefully crafted prose. Editors kept a log of some of the most embarrassing mistakes, including one by a colleague who mistranslated the German word “Schwanz”. It means tail but is also slang for penis.

CORRECTED-German Lego giraffe tail repeatedly stolen

(Correcting to ‘tail’ from ‘penis’)

BERLIN, Aug 25 (Reuters) – Visitors to a tourist attraction in Berlin have been making off with an unusual memento — the 30 cm long tail of a Lego giraffe.

"It’s a popular souvenir," a spokeswoman for the Legoland Discovery Centre on Potsdamer Platz said on Tuesday. "It’s been stolen four times now …"

The tail is made out of 15,000 Lego bricks. It takes model workers about one week to restore it at a cost of 3,000 euros ($4,300), the spokeswoman said.

Transparency and trust

Corrections are an important practice to help preserve the reputation of journalists for accuracy. However, making corrections a target that were assessed in each reporter’s annual performance review was misguided. It gave reporters – and their managers – a strong incentive to cover up mistakes. And that didn’t help foster an environment of transparency and trust. Eventually, the target was scrapped, although Reuters stuck with the policy of issuing public corrections.

Harvard professor Amy Edmondson made a name for herself by studying how teams and organisations deal with mistakes. During research into drug errors in hospitals, she came to the counterintuitive conclusion that better teams seem to make more mistakes, not fewer. She eventually realised that these doctors and nurses don’t necessarily make more mistakes, but they are more able to discuss and be open about mistakes.

Tied up in knots

Great collaboration is only possible when team members feel “psychologically safe”, knowing that “questions are appreciated, ideas are welcome, and errors and failure are discussable”, Edmondson said.

“People can focus on the work without being tied up in knots about what others might think of them. They know that being wrong won’t be a fatal blow to their reputation.”

This kind of culture is lacking in many organisations: an investigation after the Columbia space shuttle disaster in 2003 revealed that NASA group dynamics and hierachies did not encourage a candid discussion of threats.

Edmondson’s insight has since been applied in many organisations, helping to increase performance and learning, and cut errors.

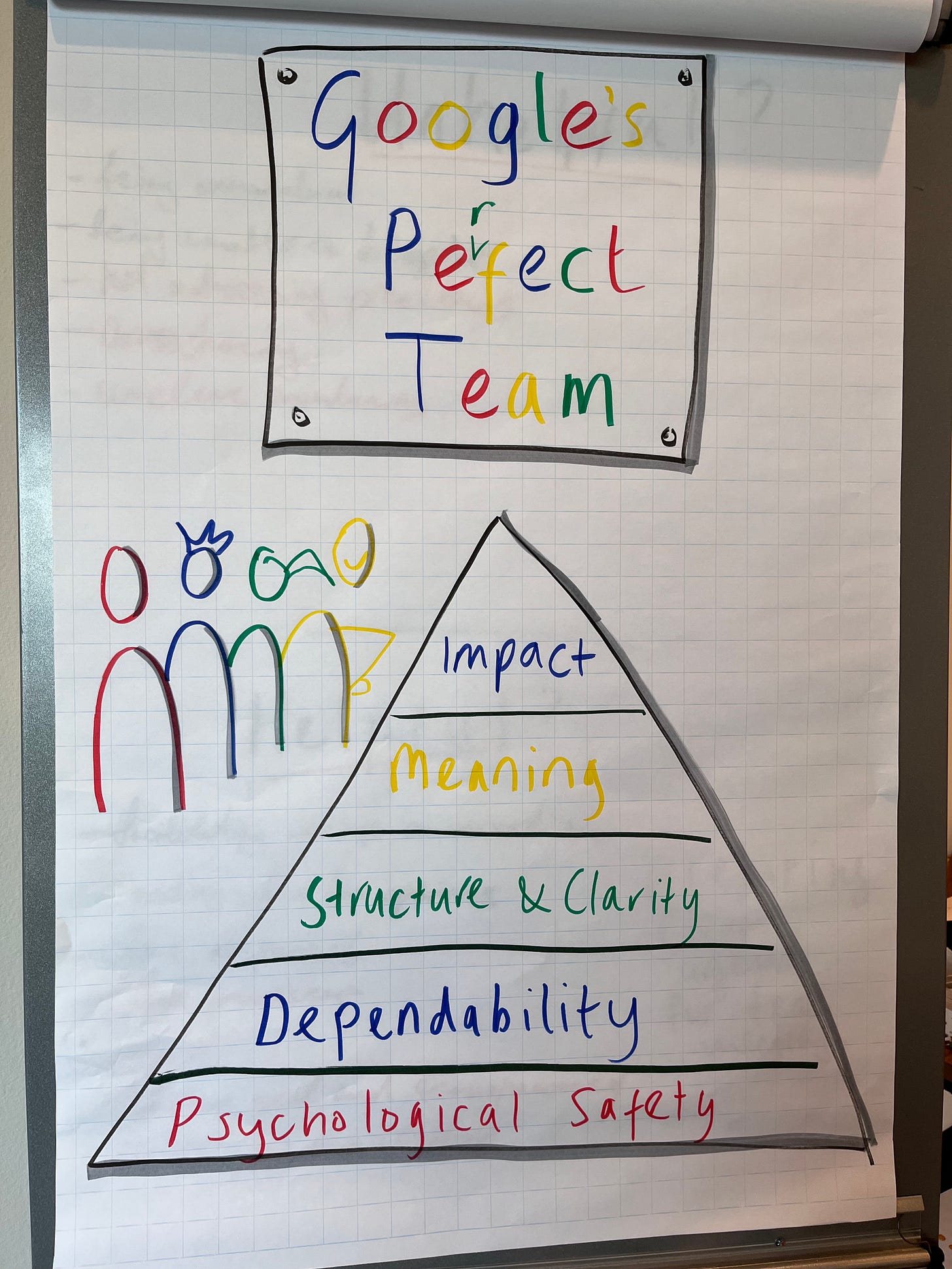

Google interviewed more than 200 teams across all areas of its business and concluded that the top-performing groups had five dynamics in common, with psychological safety the most important of them. Here is a summary:

1. Psychological safety: feeling OK about admitting mistakes, asking questions, expressing vulnerability, or suggesting new ideas.

2. Dependability: members reliably complete quality work on time.

3. Structure and clarity: a team has clear roles, goals, and plans.

4. Meaning: team members have a sense of purpose in their work

5. Impact: members believe their work makes a difference.

When I was drawing this illustration of the Google conclusions at a workshop, I made a spelling mistake. Normally, I would have started afresh, but I decided it was a good way of illustrating the importance of being open about errors.

Discussing this model at leadership workshops for newsrooms has revealed that the media industry has a very top-heavy pyramid. Teams in vocational professions like journalism usually have “meaning” and “impact” in spades. You could even argue we have too much of a sense of meaning and impact, which promotes an unhealthy obsession with work that drives us to burnout. Meanwhile, we often lack psychological safety in our teams, as well as structure and clarity.

Sometimes these factors can be at odds: so, at Reuters, the correction target my boss set gave me clarity, but it undermined psychological safety as anybody who flagged their own mistakes might be personally penalised in their annual review.

Insecure teams plagued by anxiety or apathy

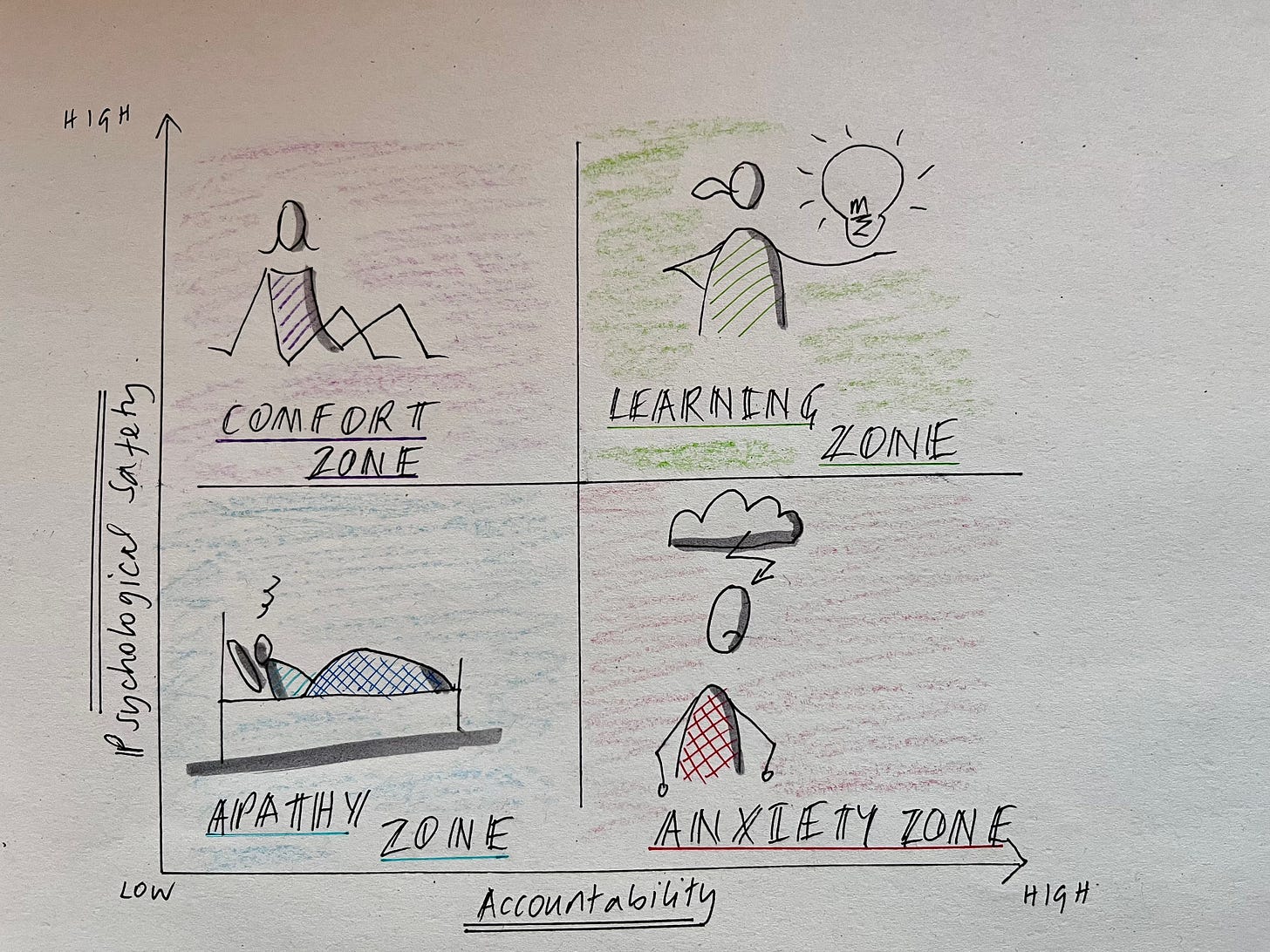

Promoting psychological safety often demands a big shift in organisation culture. If a manager wants to encourage team members to admit to mistakes or suggest new ideas, she will need to acknowledge her own fallibility and be open to constructive criticism of her own leadership. It can be time consuming to check in with team members to make sure that the psychological safety that fuels innovation is combined with accountability to turn ideas into action.

This is not about creating environments where people think it is fine to slack off, or make mistakes without consequence, the “comfort” and “apathy” zone shown above. But if colleagues get stuck in the “anxiety” zone where they are afraid to speak up or experiment, organisations will miss out on open exchange.

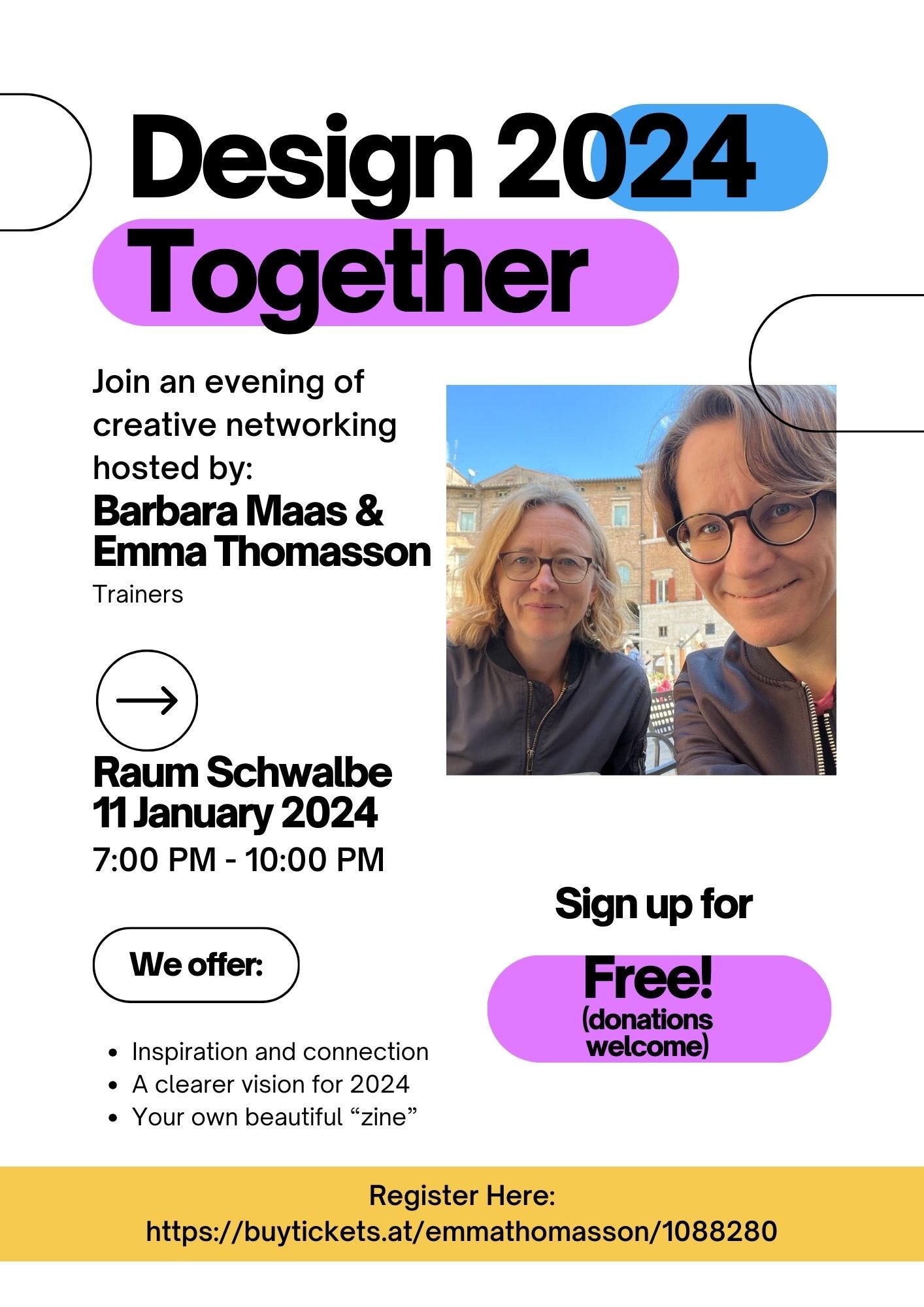

One of the most powerful ways to create that kind of environment is for leaders to show vulnerability themselves. I try to model that in my writing, coaching and facilitation work. To get a taster in person, I would like to invite readers in Berlin to sign up for an evening of creative networking on Jan. 11, when we will design our own zines, a mini-booklet that will be your personal instruction manual for 2024. Psychological safety guaranteed! (https://buytickets.at/emmathomasson/1088280)

What I am reading/listening to:

Clock Dance by Anne Tyler - a charming tale of a retired woman rediscovering purpose, community and a new direction after an unexpected phone call.

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens - after abandoning Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (an overlong modern day retelling of David Copperfield), I thought I would try the original. I am 200 pages in and still going strong!

Sideways - a lovely BBC podcast that challenges the cult of perfectionism about Mediocre Melodies - a group of average singers at Cornell University.

Great newsletter Emma, I certainly agree with the need of psychological safety. It enables not only participation but also disruptive thinking. Best wishes for your workshop, sounds great!