Culture clash: no carols at Christmas?

Or why groups of Germans take so long to reach a decision

“We don’t want to force Christianity onto the children!” That was a comment from one of the women I sing with every week in a choir. Differences between those from former Communist East Germany and those from the former West mostly go unspoken but they broke out into the open last Christmas. I kept my head down.

I have been singing for 10 years in a (very) amateur choir in Berlin. I enjoy the two hours we spend together every week. But I’m not so keen on how long it takes to decide on our future repertoire and concert dates. Everybody else seems to enjoy these spirited debates. I wish the choir master would just make these decisions for us: he is the boss after all. The discussions often become quite heated, particularly as the choir is a mix of those who grew up on opposite sides of the Berlin Wall (not that this is a divide that is openly discussed 34 years after unification).

Conflict reached a head at Christmas when the choir leader from the former West, who is an organist and loves church music, chose mostly religious songs for our Advent concert. Some of the singers from the former East rebelled and said they wanted more secular songs. If I had dared to express my opinion, I would have probably sided with the Westerners because the choir master wanted us to sing lots of my favourite British carols. In the end, the group found a compromise, but only after quite a bit of open confrontation that made me squirm.

Mapping misunderstandings

Even though I have lived in the German-speaking world for much of my adult life, I can still be blindsided by subterranean cultural differences. Such misunderstandings can make you feel like there is something wrong with yourself or your counterpart when they are often just a matter of upbringing. Learning to navigate this is essential for modern workplaces: this survey found that 89% of corporate employees serve on at least one global team, and 62% have colleagues from three or more cultures.

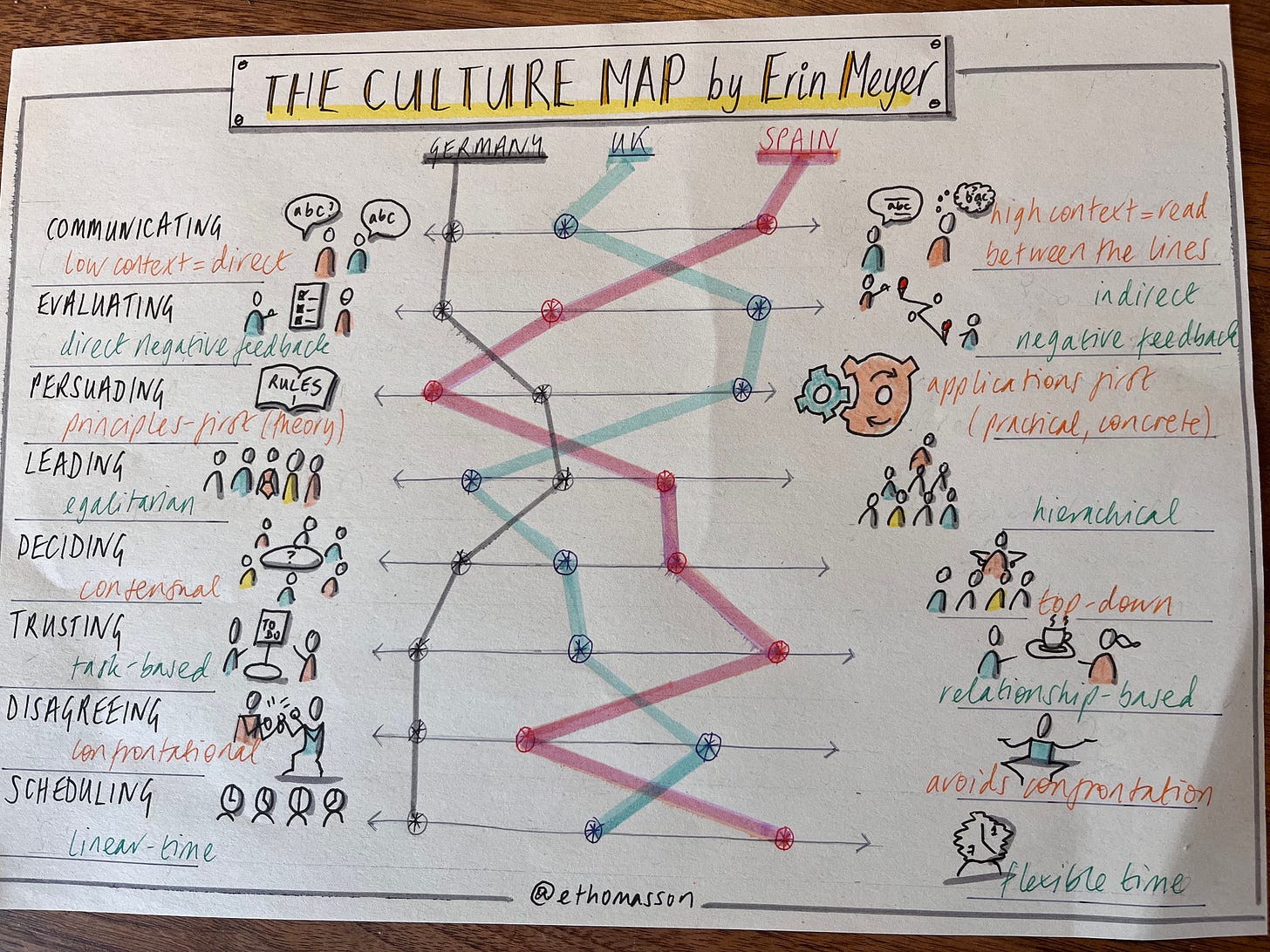

It was only when I read The Culture Map by Erin Meyer that I understood why the choir discussions are so fraught for me: they involve a culture clash on several of the eight scales she describes. Meyer maps the world’s cultures according to how people act in these areas: communicating, evaluating, persuading, leading, deciding, trusting, disagreeing and scheduling.

Here I have plotted the differences between British, German and Spanish culture: While Germans and Brits might seem like close cousins to somebody from southern Europe, Germans and Spaniards are actually more similar than you might expect when it comes to how they handle disagreements and direct negative feedback.

Conflict conundrum

Until I read Meyer’s book, I thought I was more averse to conflict than most people. But I now see that this is not just down to my personality: Brits tend to avoid open confrontation more than Germans and Spaniards (this might come to a surprise to those in Europe who enjoy Prime Minister’s Questions at Westminster). Meanwhile, Israelis and Russians are both off the scale when it comes to being confrontational, which helps explain current geopolitics, not to mention the need for the conflict management training I have been giving to Russian journalists in exile in Berlin.

German (and Spanish) organisations favour more hierarchical leadership than in Britain, but when it comes to making decisions, Germans demand a more consensual approach. Reaching decision by committee is embedded in post-war German institutions – a reaction to the authoritarianism of Nazism. Coalition governments are the norm, employees have a say in how companies are run through influential works councils, and meetings of voluntary organisations like choirs or parent school boards are often a protracted exercise in direct democracy.

Direct Dutch

With The Culture Map, I finally have a system and a language for describing, unpicking, and resolving the potential minefields I encounter daily. (As I write this on the Eurostar from Amsterdam to London, an American and a South African sitting across the aisle are lamenting the direct feedback style of a Dutch supervisor.)

The Dutch are certainly leaders in direct communication, but the Germans and Americans aren’t far behind. At a workshop on Silicon Valley facilitation methods, the trainer encouraged us to keep the discussion moving by using a card labelled ELMO (Enough! Let’s Move On). The German participants were happy to have a license to interrupt. But it felt rude for a Brit like me, who has internalised an unspoken code of stealthy passive aggression, often with a sprinkling of self-depreciation.

On the other hand, I am quite comfortable interrupting if a meeting is not sticking to the preordained agenda: what Erin Meyer calls the “scheduling” culture clash. At a workshop in Rome for mostly southern European broadcasters, I couldn’t control my clock watching (probably heightened by living in Zurich for 5 years). I took over time keeping for the group, using the grating alarm of my phone to make sure that each participant did not speak for longer than 5 minutes. The Italian moderator of the event said she was grateful because she said she found it too rude to interject, but I suspect most of the participants found my approach rather brash.

I have already written about my experience of Spanish time, but looking back I realise I made an unconscious value judgement about northern European “efficiency”. I now understand that people who have a more flexible approach to time, like those from southern Europe and southern Africa, see us chilly northerners as rigid and potentially inefficient because our linear planning systems do not respond well to the unexpected.

Mañana Mentality

We are trying to use SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-Limited) for the gender equality project I am working on with public broadcasters. But my understanding of a time limit is different to that of the Italian manager I am mentoring. It might look to me that her timetable keeps slipping, but her perspective is that she is changing it to adapt to new challenges and opportunities.

Our different appreciation of time also intersects with the culture clash between northern and southern Europe when it comes to how we build trust. The Spanish, Italian, French and Croatian newsroom leaders in Rome were keen have another glass of wine at 11pm, while the lone Brit (me) and Swede wanted to get back to the hotel so we could meet refreshed for a second day of workshops. Northern Europeans tend to build trust by getting the task done (on time) instead of by schmoozing in the bar. However, this is all relative of course: compared to Germans, British relationships of trust are very relationship focused, often involving a cup of tea and cake.

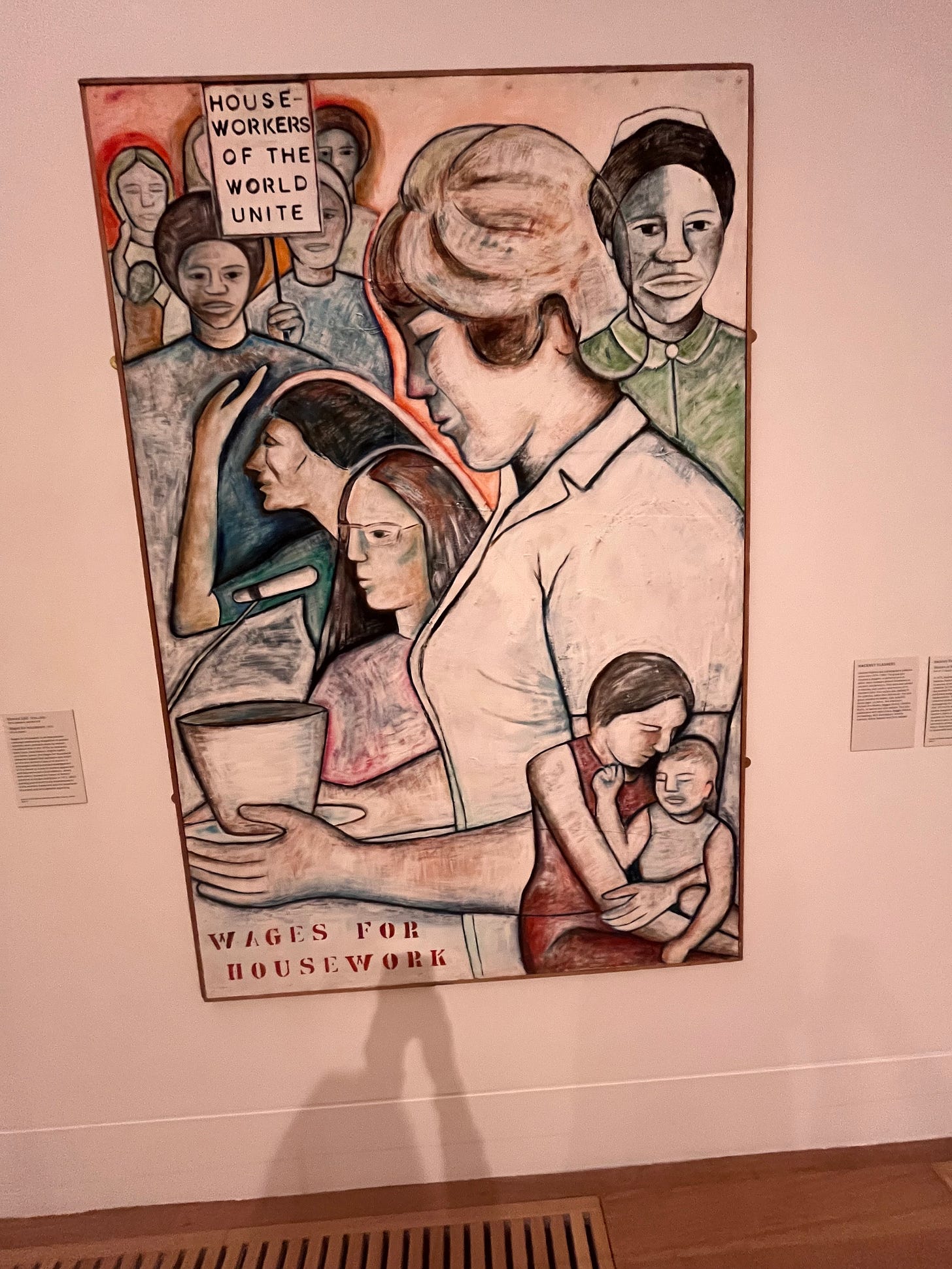

Gender gap

The only gap in Meyer’s book is that it does not explore how gender intersects with national culture. My gut says that women often feel the need to use a more indirect communication style in professional settings. And a woman boss might not be as free to give direct negative feedback or to be confrontational as her male counterpart due to gendered social norms that demand that women appear “nice” and “caring”.

No doubt we will be addressing some of these questions in the “Woman on Purpose” programme of group coaching and workshops I am launching on April 10 with five women from five countries who I met last year on a fellowship in Spain. We are a Brit, a German, a Belgian, a Venezuelan, a Canadian and a Colombian and we guarantee a high-level of sensitivity to cultural differences.

I will keep digging into these issues in future blogs. Writing this has clarified that bridging cultures, personality types, genders and generations is my calling, which is why I have decided on a new name for this newsletter, a year after I launched it,

I am calling it Bridgit: psychology, leadership, change, to reflect my focus topics and expertise. Bridgit is the patroness saint of Ireland, where some of my ancestors hail from, and is derived from a Gaelic word meaning power, strength, vigor and virtue. It is also my mother’s middle name. Thanks Mum for the inspiration!

What I am reading:

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer - a novel that follows the lives of six American teenagers who meet at a summer camp in 1974. It explores the damage caused by jealousy and secrets, but is ultimately about the special bonds of friendship forged in our teenage years.

Ritual by Dimitris Xygalatas - a gripping account of why supposedly rational humans are hardwired to create and benefit from apparently irrational rituals and ceremonies by an anthropologist who studies communities that practice fire walking.