I met a former police officer recently who used to work in counter-terrorism. “Your job must have been stressful,” she said to me. “How did you handle so much bad news?” That brought it home: a police officer thinks that dealing with news all day is more onerous than risking her life chasing bad guys.

How much time do you spend consuming the news each day?

How much time did you spend before the Internet, if you’re old enough to remember?

If you’re a journalist, how much news do you need to be good at your job?

I have been asking myself these questions as I grapple with the topic of news avoidance that poses an existential threat to the media industry.

The last article I wrote for Reuters in 2022 was a round up of that day’s fighting in Ukraine. When I left, I was sad to be missing out on reporting on this crucial story and leaving my colleagues. But I also felt a mixture of relief and guilt. At least I could take a break from watching and writing about suffering every day.

Does that make me a bad journalist? Or a bad citizen - or a bad person?

The news habit

Am I less well informed than I used to be when I spent almost all of my waking hours marinating in the news? How much time should journalists, and everybody else, spend on the news?

For most of my adult life, apart from holidays and two maternity breaks, I ate, slept and breathed the news, particularly global politics, diplomacy and business. Before news went digital, that meant a daily routine of “reading in”. I was expected to listen to the radio over breakfast and then scan about 10 physical newspapers in the office before sitting down at my desk.

This was drilled into me, and many other trainee journalists, by the intimidating Bonn bureau chief Tom Heneghan, who would fix you with his steely blue eyes. He would not be impressed if you missed a key interview. For years, I was mainlining 10-14 hours of news a day.

My childhood had prepared me well for this routine: I grew up in a household where BBC Radio 4 was constantly on in the kitchen, the Guardian newspaper on the table and we all watched the TV news together in the evening. Nowadays, my 81-year-old father still has BBC news alerts pinging on his phone throughout the day.

But after half a lifetime of doomscrolling at Reuters, I wanted a break from the news. I wasn’t even sure I wanted to stay in journalism. And I know I am not alone: it is our industry’s dirty secret - many of us don’t buy our own product.

The (news) customer is always wrong

This is a painful message for journalists but one we know in our hearts. “When did you last pay for news?” I challenged economics journalists from across eastern Europe at a recent workshop. A couple of them subscribed to the New York Times or the Economist online, but few of them paid for news from their own region.

“Journalism has to stop being the only industry where the customer is always wrong,” says Shirish Kulkarni, a journalist, researcher and community organiser from Wales.

Nowadays, I spend most of my time advising the media on how to tackle news avoidance and supporting frazzled editorial leaders and journalists rather than producing or consuming much content myself.

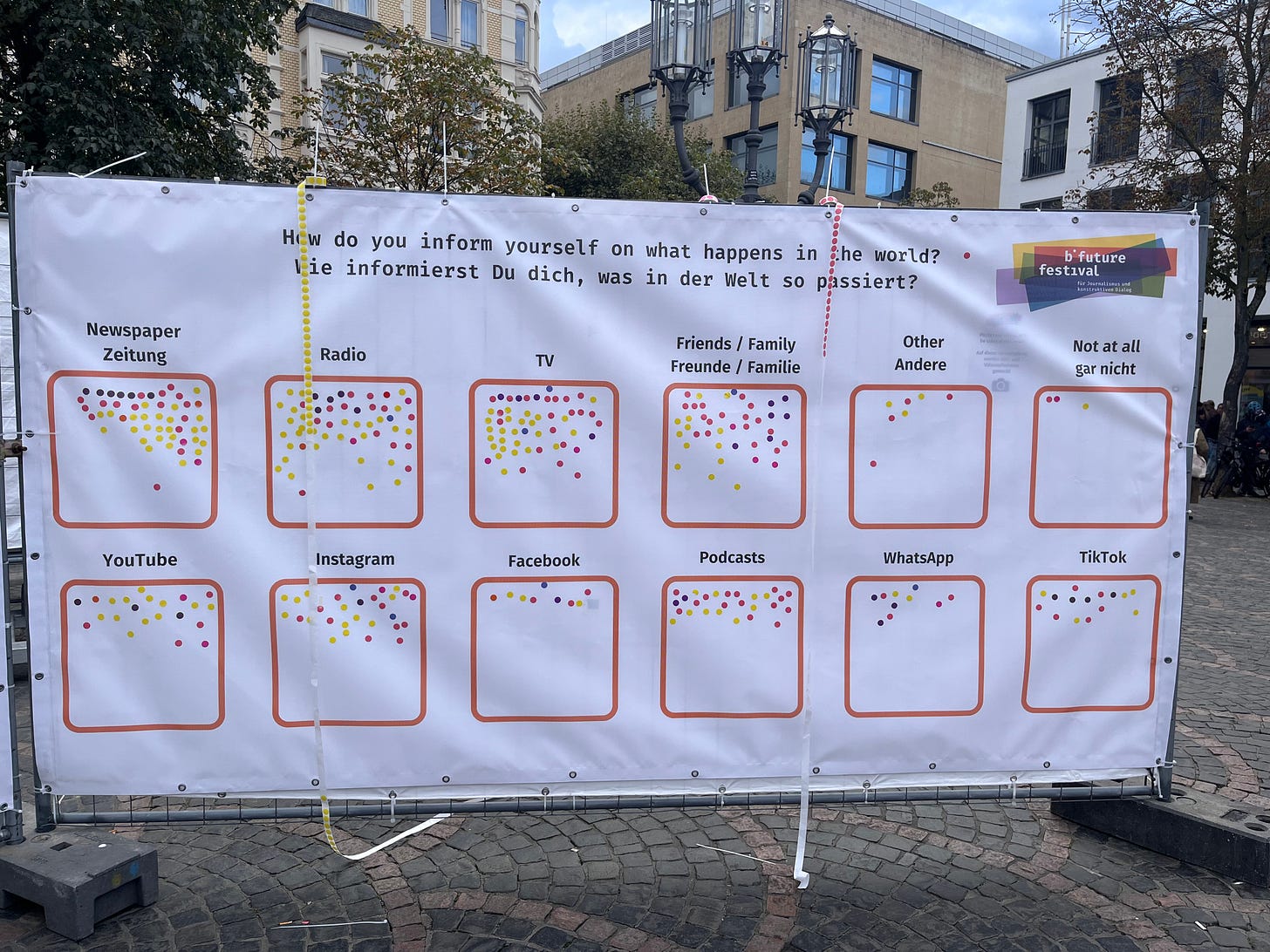

Since I left Reuters three years ago, I am probably down to under an hour of news a day, except on the days when I am doing freelance reporting. Meanwhile my teenage sons catch a few minutes of BBC radio while inhaling porridge, spend a few minutes a day scrolling past the news on social media and occasionally pick up the Week magazine that I strategically leave open at articles about sport and popular culture. But they do often seem to pick up on world events faster than I do. “Did you hear how horrible Trump was to Zelensky?” one of them asked soon after the infamous confrontation at the White House.

I definitely know less about government policy than I used to, but I have more time and mental space to read long-form journalism, academic articles and non-fiction books. And I have more time to think and write myself, and to talk to friends who are artists, teachers, scientists and entrepreneurs, rather than journalists or politicians.

So I might know less about the details of the German coalition negotiations, but I have a better idea of the impact of cuts to the arts in Berlin, for example. In the recent German election, I ended up voting for the same party I always support, like most people. After all, if we are honest, voting is a often a more tribal decision than one based on careful analysis of party manifestos.

Making our hobby our job

Political scientist Eitan Hersh says many people are political “hobbyists” – we might obsessively follow the news and complain about it, but the time we spend thinking about politics is not much more than a way to pass the time. Instead, he argues, we should be spending our time “doing politics” rather than talking about it. Journalists might think we are exempt from this exhortation, but most of us have just made our hobby our job and that shouldn’t exempt us from our obligations as citizens.

“Citizens who want to empower their political values would be better off if they spent less time consuming politics as at-home amateurs and instead fell in line to help strengthen organisations and leaders,” Hersh writes in Politics is for Power.

“When we are disturbed by the news, we may feel that we need to do something, but the only something we can think of doing is reading more news.”

Germany’s Katapult magazine makes a similar appeal: don’t just vote, but join a party, support a trade union or a youth club, boost local journalism, protest or join the “Grannies against the Far-Right” organisation!

Trump: 1 Journalism: 0

Among journalists and other politics junkies, there is a huge amount of guilt around news avoidance: in a recent workshop on burnout I was moderating, one fact-checker says she tries to switch off from the news at home, but her friends and family want to hear her opinion on the latest Trump falsehood. Many journalists are falling into the trap set by Trump, and now copied by other populists, to “flood the zone” with a stream of policy initiatives and announcements designed to sow confusion and distrust. And that is making for worse journalism and unhappy journalists.

Many journalists feel they would not be doing their jobs properly if they don’t follow every new outrageous policy so they don’t allow themselves the downtime they need to recover and risk burning out and eventually leaving the profession.

Read less, know more?

News avoidance is obviously a problem for the business of journalism but is it necessarily a problem for our societies and democracy?

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism has been tracking a steady rise in news avoidance in the last 10 years, especially among younger people and those without a university degree. But it is difficult to prove that most people are less well informed as a result. For example, does it matter if they found out about the scandal around the UK Post Office wrongly prosecuting subpostmasters via the hit TV drama, or via years of investigative journalism from the satirical news weekly Private Eye?

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, the Institute’s former director who is now professor of communication at Copenhagen university, told me it is possible that people’s news needs are being met more efficiently in the digital age, so they might not need to spend so much time to find the information they care about.

That is true of my new favourite news app The Knowledge that collates highlights from a range of major news sources and social media into a 5-minute daily digest and concludes with a satisfying message: “That’s it. You’re done”. No mindless scrolling.

However, Nielsen is concerned about rising information inequality, suggesting that following the news might end up as an elite pastime:

“with a role akin to contemporary art or classical music: highly valued by a privileged few, regarded with indifference by the many.”

Is more news good news?

If more news is not always good news on a personal level, or even a citizenship level, is it even the right answer for the news business itself?

It is often difficult to disentangle news avoidance from attempts to wean ourselves off our digital addictions more generally. It is ironic that the Guardian has launched The Overwhelm project to help people cope – as if more content is the answer. (Of course, dear reader, my newsletter is the exception.)

“There is not a single reader, viewer or listener asking for MORE, or CHEAPER content,” says Kulkarni, rejecting suggestions that the answer to the news industry’s malaise is to pump out lots of stories generated by AI.

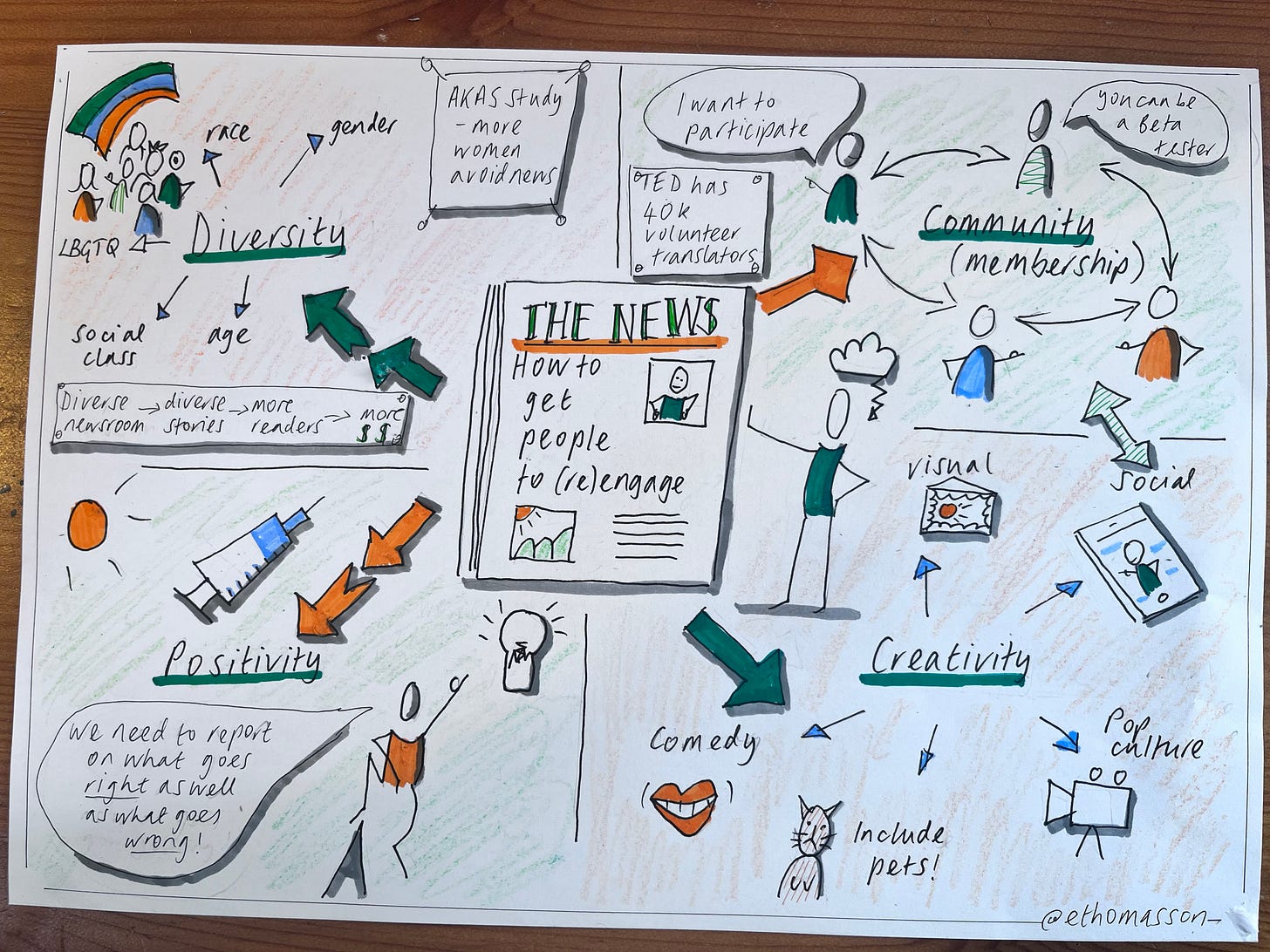

“What our citizens are telling us is that they want us to connect and share with them – to deliver journalism built on the uniquely human characteristics of connection, collaboration and care – that makes their lives better, easier and more enjoyable.”

That is exactly what two news projects I am supporting are trying to do by building a community around content closely tailored to their audience’s interests, for hyperlocal news in a region of Poland, and for 18-30-year-old women in Romania.

That is also what many of the best newsletters I follow are aiming for. My current favourites are by

, , , , , , and .When I look at that list I realise I am still spending quite a lot of time reading a kind of journalism, even if it isn’t classical news. I have inadvertently curated for myself the equivalent of a new publication tailored to my interests of leadership, media, the workplace and psychology. Perhaps I am not really a news avoider after all?

What new writers, news sites, podcasts or newsletters can you recommend?

Hi Neil, thanks for sharing your post and particularly your reference to the Taiwan study about altruism and constructive news and video games. Perhaps if I can get my son off Fortnite, he will be more likely to stack the dishwasher!

"Positive, uplifting news can inspire more altruistic action than news which leans more on negativity. This finding echoes research into the effects of consuming prosocial versus violent content in video games and entertainment: prosocial media is associated with increased empathy and helping behavior."

Hi Emma, I really love this piece. So interesting to read your perspective on switching-off.

I also read the Reuters 2024 Report with interest, but I wonder if we lose something when we stop consuming mass media?

I looked at some studies on this topic in my post yesterday: Why Read The News?

There's lots of interesting data about empathy and altruism in the research. And most of it matches what Susan Sontag was talking about back in 2003.

I'd love to know what you think!

https://open.substack.com/pub/neildillon/p/why-read-the-news?r=1ok77x&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false